Italy is world renowned for its history, art and food. The allure of its well preserved remains of the majestic Roman Empire and the renaissance art inspired by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo dates back several centuries. Add to that, the lure of contemporary popular dishes (pizza, pasta), fashion houses (Prada, Gucci) and supercars (Ferrari, Lamborghini) and Italy has something for everyone. It is home to the snow-clad mountains in the North, the sun-soaked beach towns in the South and a plethora of UNESCO World Heritage places like Venice and Pisa in between. It is no wonder that tourists flock in record numbers to this wonderful country. Like any other country, Italians have their share of differences, most notably the age old North-South divide and of course, their soccer rivalries. But just like the Azzuri (Italian national soccer team) manages to bridge all these difference and bring everyone together during a World Cup (sorry 2022!), there’s one more unifying force amongst Italians – their love for cinema.

Italian cinema has been highly underrated of late, which wasn’t always the case. In fact in the history of Oscars, Italy has won more awards in the Best Foreign Film category (14) than any other country. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, given their rich filmmaking tradition. Of note is the neorealism movement during the post World War II days when the country was breaking free from Mussolini’s fascist rule. Movies such as Roberto Rossellini‘s Rome, Open City (1945), Vittorio de Sica‘s Bicycle Thieves (1948) and Federico Fellini‘s La Strada (1954) and Nights Of Cabiria (1957) focussed on the struggles of the common, working class people dealing with consequences of the war such as poverty and loss of simple values. One movement gave way to another in the ’60s when Sergio Leone‘s ‘spaghetti’ westerns breathed new life into the genre. Leone’s iconic ‘The Man With No Name’ trilogy featuring A Fistful Of Dollars (1964), For A Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good. The Bad And The Ugly (1966) made Clint Eastwood a household name. In recent years, Robert Benigni and Giuseppe Tornatore have carried the torch forward for Italian cinema.

While growing up in India, I hardly watched foreign films. Hollywood itself was a rarity. The only Italian movie that I had seen (and liked) back then was Roberto Benigni‘s Life Is Beautiful (1997) which had won that year’s Academy Award for the Best Foreign Film. I have described in another post how my movie watching experience expanded significantly after moving to the US. It was in that same summer of 2004 when my Italian neighbor and good friend Vincenzo recommended Cinema Paradiso to me. His superlative praise for the movie had definitely piqued my interest and it ended up being one of the first (of several) DVD purchases in my collection.

Comments:

Cinema Paradiso is a love story. It is the tale of Toto, a young boy who falls in love with movies in his small Sicilian town of Giancaldo and the deep bond he forms with Alfredo, the projectionist of the town’s only cinema hall – cinema Paradiso. The movie opens with Salvatore (a grown up Toto in his 50s), who’s a successful film director in Rome, getting the news of Alfredo’s death. This brings back a flood of memories for Salvatore who was raised by his mother in a post-war Italy and for whom Alfredo was like a father figure. Through a flashback, we visit the 1940s Giancaldo where Toto is an 8 year old mischievous altar boy. Like most kids of his age, Toto is bored with the usual duties like assisting in prayers and religious ceremonies but there lies a secret bonus. Being always around, he secretly watches all the movies that come to town during their private screening for the priest who decides what is suitable for the audience. This censorship of the church was a common phenomenon in a Catholic dominated Italy of the mid 20th century. In the Italian comedy Divorce Italian Style (1961), the church is also seen denouncing the Fellini classic La Dolce Vita (1960) for corrupting the society with its racy content. Toto finds this whole exercise of editing out the “indecent” kissing scenes fascinating. Similar to how a kiss that’s shared by the on-screen characters is an intimate moment to be savored by no-one else but them, this is a special memory for Toto. It is a secret that only he is privy to and an experience that’s just his to cherish. He hounds Alfredo for the discarded film that ends up on the cutting floor for his own collection. In this era of digital projection and streaming, it is a rare chance for the audience to see older technology of film reels and the physical film stock being inspected and cut by hand.

The bond between young Toto and a doting Alfredo forms the crux of the movie. Toto is shown to be very curious and has a vivid imagination. Watching a film in the cinema hall is the highlight of his day. He is no ordinary fan though. While the rest of the audience is glued to the on-screen action, Toto wants to find out how the magic is created in the projector room. The inquisitive kid tries every possible trick in the book to learn from Alfredo – by asking him outright, by peeping into the room through the projector hole when Alfredo’s not looking and even entering the room under the pretext of delivering lunch. But Alfredo doesn’t budge and always discourages Toto from hovering around the projector room. There are two reasons for his reluctance – the flammable nature of film in those days and the associated risk of fire1 and his belief that Toto’s future lies in the wide world outside Giancaldo and not inside cinema Paradiso’s projection room. One evening, Toto spends the money saved by his mother for daily essentials on a film and gets caught. Only some quick thinking on Alfredo’s part saves him from his mother’s beating. While Alfredo is only pushing him to aim higher and achieve bigger things, he is also aware that cinema is Toto’s true calling and finally gives in to the persuasive kid.

Speaking of the theater, cinema Paradiso is almost like a major character in the movie. It is an indoor town square where people from all wakes of life come together to have a good time. Over the years, we see people from the audience meet, fall in love, get married and have kids. While most people come to enjoy the movie, there are some who come to sleep, especially during a double feature. In addition, there are legit and not so legit side deals that are struck inside the cinema hall. Here, we get to experience the mood of the town – people laugh at the antics of Charlie Chaplin, dance to the tune of El Negro Zumbón2 and ride the emotional upheaval of the family in Catene (1949). The collective anticipation and disappointment at a kiss not shown or an intimate scene cut short is palpable. The power of films to make its audience cry or laugh is evident every evening inside this small theater. As the war rages outside, residents of Giancaldo see the world through the lens of cinema and get their news from the newsreels that play at the beginning of films. The theater is an integral part of their daily lives. It is a place where they go about their personal and private business, in hiding or in plain sight. From the weddings of its patrons to their funerals and from silent movies like The Gold Rush (1925) to outdoor presentations like Ulysses (1954), cinema Paradiso has seen it all and shown it all.

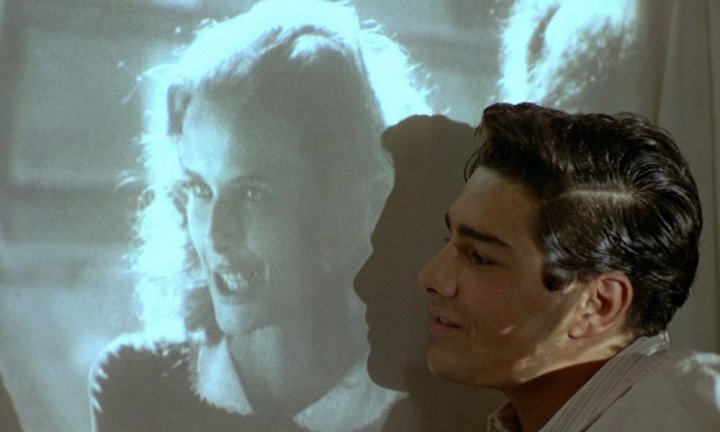

Fast forward a few years and another flashback takes us back to Giancaldo where Toto is now a teenager. As Toto has grown up, the town and cinema Paradiso itself have undergone some significant changes. The film used in projectors is fire resistant now and the censorship guidelines have been relaxed so much that people finally get to see on screen kissing! While still working as a projectionist, Toto is seen dabbling into making his own home movies. Through the lens of his 8mm camera he begins to notice the world around him in ways that he had never experienced before. The simple joys of childhood are replaced with the intense feelings of love, heartbreak and desire. To add to these turbulent changes in his life, he gets recruited into the army and on his return after about 18 months, finds out that Giancaldo of old is no more. But through all this, the bond between Toto and Alfredo not only survives but grows stronger. Alfredo had warned him of exactly the same thing and after realizing that he will have to leave everything behind to fulfill his calling, Toto makes the ultimate sacrifice

This phase of the movie beautifully manages to capture the essence of adolescence. A teenage Toto is full of energy and hope for his future but finds himself at crossroads after returning home from military service. When everything seems lost, it is his friend and mentor Alfredo who once again guides him and channels his energy in the right direction. During their intimate talks, Alfredo, who’s probably never ventured far away from their small town, gives worldly wisdom to Toto for whom life holds infinite possibilities. It may seem a little harsh to the audience to see Toto act on his advice about leaving town and never to return. But one should realize that Alfredo has been the only father figure he’s had in his life and who’s stood besides him through all the ups and downs. All his life, Alfredo was responsible in a certain way for bringing joy to him and all the people of Giancaldo by playing hundreds of movies and catering to their emotional needs. It is now time to return the favor. Toto’s journey is not just for himself, but also for the misfortunate Alfredo who’s never had a chance to explore his own potential.

Salvatore’s return to Giancaldo, a place that he left as teenaged Toto, has a very nostalgic feel to it. Anyone who’s been away from their hometown knows the mixed feelings they encounter upon their return. The places frozen in their memories have been reshaped by many small and large changes and the bonds that tied them together deteriorate over time3. But it’s a little different with people, especially the ones close to us. There’s a nice scene where the cab drops Salvatore off at his home. Sensing his arrival, his mother drops the sweater that she’s knitting and runs to meet her son who’s returning after over three decades. She accidentally carries the yarn with her and the meticulously woven fabric simply comes apart in a jiffy symbolizing her emotional state which she had held together for so many years, only for the dam to break and a deluge of memories to come pouring in. Finally for Salvatore, It’s a bittersweet visit to his hometown. Arguably, the strongest connection to his past and the driving factor behind his success is no more, but a special gift that Alfredo leaves behind for his beloved Toto is something that he will treasure forever.

Cast and Crew:

The director Giuseppe Tornatore was himself born in Sicily and just like Toto, was a huge fan of films as a child. He ably transports his audience into his childhood via this semi-autobiographical movie. Both the main characters have been well fleshed out and their strong bond is evident. Similar to how Alfredo says something profound and immediately follows it up by attributing it to some Hollywood actor, Mr. Tornatore evokes some deep emotions, often with the help of humor. He was a frequent collaborator with the music legend Ennio Morricone (The Good, The Bad and The Ugly fame) including on this film and has made a documentary Ennio (2021) celebrating his life and career. It is hard to imagine Cinema Paradiso without the excellent accompanying soundtrack provided by Mr. Morricone in which he captures the essence of small town Sicilian life and the various moods of its two protagonists. Just listen to one of my favorite themes from the movie – Team d’amore.

Toto has been played by three actors in various stages of life and all three do justice to the character. Salvatore Cascio plays the 8 year old mischievous Toto who’s as inquisitive as he’s naughty. The selection process for this part included a rigorous audition of over 200 boys. As he mentioned in an interview4, he did win the role but lost a friend who was the only other finalist with him. Marco Leonardi plays Toto in his teenage years with the right amount of intensity and energy. His heartfelt chats with Alfredo are some of the best scenes in the movie. And finally, Jacques Perrin plays the adult Salvatore. He portrays the emotional turmoil of the character returning to his roots after a long gap with a suitably reserved and pensive demeanor. The role of Alfredo is played by the French actor Philippe Noiret. Even though the chemistry between his character and Toto is evident and is the focus of the movie, one may be surprised to know that Mr. Noiret could barely speak Italian. The magic was made possible with the aid of a translator and dubbing artist.

Multiple Versions:

One thing that’s worth mentioning is that there are three versions of this movie of varying lengths. As one might rightly guess, the longer version includes additional footage that was left out from the other releases. But the nomenclature is a bit confusing and it needs a little more context to understand the differences between them. In 1988, the 155 minute version5 of Cinema Paradiso was released in Italian theaters. This was the first released version of the movie and unfortunately received lukewarm response from the audience. So to appeal to the worldwide audience (and specifically in the US keeping an eye on award considerations), a decision was taken to condense the runtime to 124 minutes. This shortest version that saw a theaterical release in the US (and international markets) was the one that became hugely popular and went on to win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film at the 1990 Oscars ceremony. Due to its widespread fame, it is now referred to as the “Original Version”. Over a decade later, owing to its sustained popularity, Miramax films released the complete version on DVD that was 173 minutes long and marketed it as the “Director’s Cut” or “The New Version” here in the US. It is interesting to note that this longest version not only adds more context around several scenes but also changes the flavor of the movie. While the shorter version shows the love story between Toto and Elena only during his teenage years, the focus largely remains on his passion for cinema and the bond between him and Alfredo. On the other hand, the longer version fills several gaps in Toto and Elena’s love story and we ultimately find out what happens to their unconsummated love. For me personally, this closure is satisfying in a way but it does take away the impact of the shortest “original” version. Sometimes less is more and specifically with this film, editing out large chunks of the story is probably for the best. My recommendation would be to watch the hugely popular and impactful “original” version first and then the “new” version to satisfy your curiosity.

Final Thoughts:

A throwback to the golden days of Italian neorealism films of the 1940s, Cinema Paradiso is Mr. Tornatore’s ode to cinema halls and filmmaking. It is a tribute to that special place held by a movie theater in the minds of many people across generations before the advent of television. Anchored by solid acting performances and Ennio Morricone’s haunting score, this is one of my favorite movies of all time. A must see for any cinephile and highly recommended for all.

1 Until 1950s, the majority of film stock was made of a material called nitrate which was highly flammable and required careful handling and storing methods. Here’s a comprehensive article from BFI (British Film Institute) that goes into details of storing old films.

2 El negro zumbon is a very popular Spanish song from the movie Anna (1951). It was also heard playing in the background during the restaurant scene from The Irishman (2019) when Frank is introduced to Russ.

3 Thankfully, all is not lost of the cinema Paradiso. We can still visit the cinema hall of Toto’s childhood at the Museo Nuovo Cinema Paradiso near Palermo in Sicily.

4 An interview with Salvatore Cascio published in Cineaste magazine can be found here.

5 The 155 minute version of the movie is not in mass market circulation and is rarely available to watch in theaters during special screenings.

Leave a comment